On Oct. 7, 2022, a seemingly obscure corner of the U.S. Department of Commerce, the Bureau of Industry and Security, delivered a seismic shockwave to the global semiconductor industry. It did so by announcing stringent, unprecedented and unilateral American export controls on advanced computing and semiconductor manufacturing equipment destined for China. Just a little over a year later, on Oct. 17, 2023, the same bureau further strengthened its unilateral restrictions on such exports to China.

Now that we have had time to evaluate the results of this watershed moment, it is imperative that America charts a new course toward a robust semiconductor strategy to safeguard our national security and our economy.

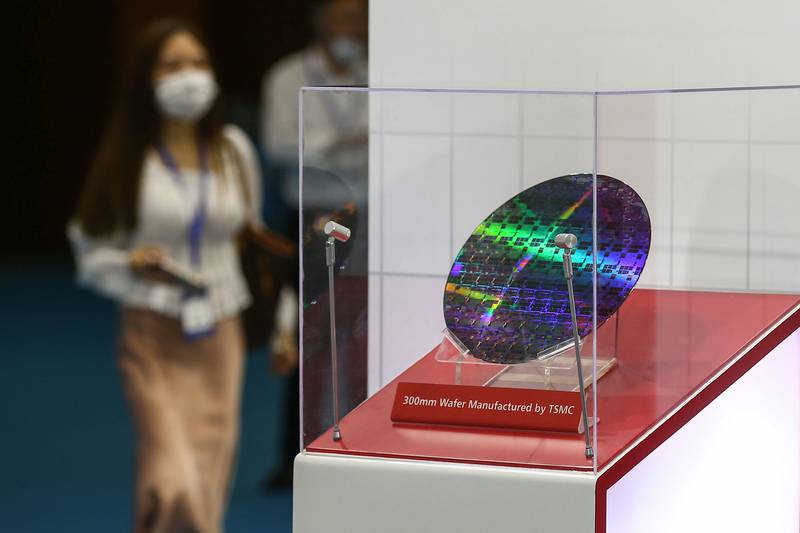

Today, China and Taiwan combined have nearly three quarters of the global market share of semiconductors, which poses a threat to the U.S. economy and its critical military products and systems. Recent international developments have cast a stark spotlight on the decided deficiencies of the current global, voluntary export control framework known as the Wassenaar Arrangement. Russia’s brazen invasion of Ukraine and China’s multifaceted gray zone war against Taiwan have laid bare the shortcomings of this voluntary association.

In this era of relentless global geopolitics and intense technological competition, we find ourselves at a pivotal juncture where the bedrock of our future security lies in a semiconductor treaty firmly rooted in the Wassenaar Arrangement but fortified with substantial revisions, all with a keen focus on the indispensable semiconductor industry.

The Wassenaar Arrangement, conceived as a voluntary global export control alliance, was designed to facilitate information exchange among member nations regarding technologies, including semiconductors, that have military or military-civilian applications. The goal, as articulated by the Arms Control Association, is to promote “greater responsibility” in military exports and prevent “destabilizing accumulations” of weapons. This arrangement was never intended to target specific regions or groups of states, and members lacked veto authority over each other’s exports, rendering it a voluntary association.

The United States, alongside 41 other nations, stands as a member, while Russia, also a member, has repeatedly exposed the inadequacies of this voluntary accord. The absence of a robust global semiconductor export control regime leaves the United States vulnerable in the technological race, especially as China, conspicuously absent from the Wassenaar Arrangement, seeks to surge ahead.

The time has come for the United States to lead the charge in crafting an international treaty governing the export of advanced semiconductors, involving key allies that constitute the backbone of the semiconductor supply chain: Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea and Taiwan. This coalition can fittingly be christened the “Semi Allies Group.”

We must elevate the Wassenaar Arrangement to the status of a binding Wassenaar Treaty, targeting nations such as China, Russia, Iran and North Korea, which pose military and economic threats to the founding members. Our primary focus should be on semiconductor technology, a linchpin of both our economic prosperity and national defense. This treaty framework would grant each member veto authority over another member’s proposed exports.

Converting parts of the Wassenaar Arrangement into a specialized treaty would address its glaring inadequacies by concentrating on the key semiconductor supply chain leaders, honing in on a single critical technology, targeting a specific group of destabilizing nations and providing all participating members with the much-needed veto authority.

The existing U.S. tactics of unilaterally imposing ever-stricter unilateral export controls on domestic companies selling to China, combined with efforts to persuade other key nations to follow suit, is far from ideal for American military defense and its semiconductor businesses. They cannot rely on the United States indefinitely convincing foreign competitors — particularly in export-driven economies like Germany, the Netherlands, South Korea, Japan and Taiwan — to refrain from selling advanced semiconductor technology to China. The U.S. military should support this multilateral treaty approach because it keeps the most advanced technology out of the hands of our fiercest foes.

Likewise, U.S. semiconductor businesses should also rally behind this approach, recognizing that if they are barred from exporting a specific semiconductor technology to China, their primary commercial rivals will face similar restrictions.

The geopolitical landscape has undergone profound changes, with NATO uniting against Russia’s Ukraine invasion and the Quad — comprising the U.S., Japan, India, and Australia — aligning to counter China’s expansionist ambitions. These developments present golden opportunities for multinational cooperation in matters of defense.

The establishment of a Wassenaar Treaty will not be without challenges, such as securing a two-thirds vote in the U.S. Senate. Nevertheless, it is a challenge worth pursuing. Bipartisan support for the CHIPS and Science Act as well as shared concerns about China’s threat to Taiwan suggest the political will may exist at this critical juncture in time.

RELATED

Effective export controls on semiconductors within the Semi Allies Group, under the proposed Wassenaar Treaty, could pave the way for the inclusion of other critical aspects of the global semiconductor trade. The Biden administration’s efforts to coordinate subsidies supporting specific members of the Semi Allies Group’s industrial policies align with the goal of promoting domestic semiconductor manufacturing, thus averting production surpluses or redundant government investments. This subsidy coordination could also become an additional focus under the treaty.

Furthermore, the Biden administration’s recent executive order issued on Aug. 9, 2023 — instructing the Treasury Department to develop regulations prohibiting American investment in certain advanced technologies, including semiconductors, in China for military purposes — underscores the necessity of multilateral, coordinated restrictions on outbound investments in China among the Semi Allies Group. This ensures that U.S. private equity and venture capital are not unfairly disadvantaged while their counterparts in other member countries remain free to invest. This, too, could become another facet for the Semi Allies Group to coordinate under the treaty.

The time has come for the United States to take resolute action in safeguarding its national security interests. The vulnerabilities of the Wassenaar Arrangement have been laid bare by recent events. We have witnessed the consequences of timid responses to Russia’s invasions of Moldova in 1992, Georgia in 2008 and Ukraine in 2014. We cannot afford to be complacent. By establishing a Wassenaar Treaty with a laser focus on semiconductors, we can address the glaring gap in our export control framework for this critical technology. The moment has arrived to secure our technological edge and protect our nation’s future. The time for action is now.

André Brunel is an international technology attorney with Reiter, Brunel and Dunn. This commentary was adapted from his article published in the Journal of Business & Technology Law. The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are his and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the law firm or any clients it represents.