COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — During a meeting with Space Force officials this month, members of Firefly Aerospace’s team received text alerts saying their Alpha rocket needed to be ready to launch a military mission within 24 hours.

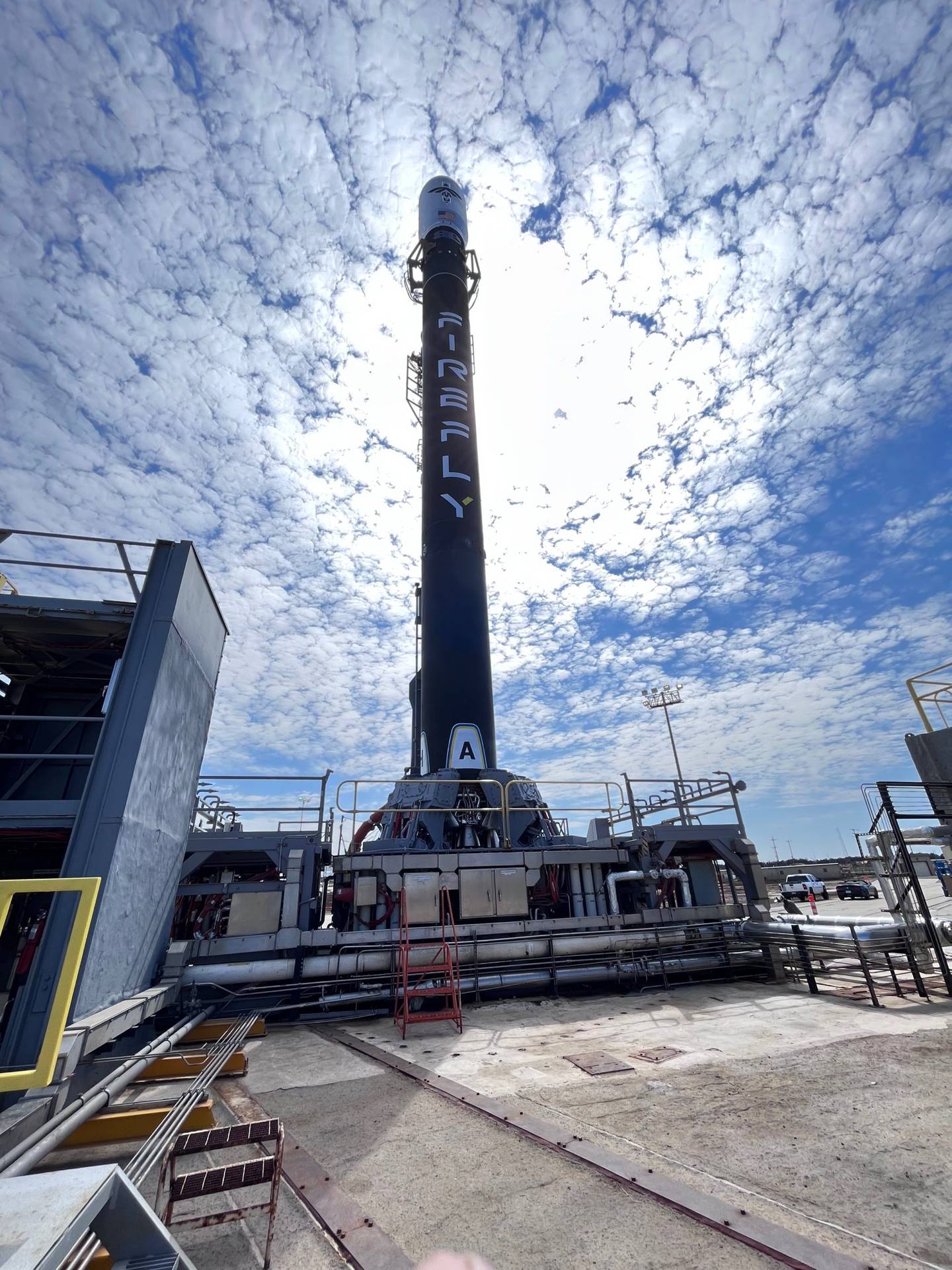

The message was just a drill, according to CEO Bill Weber, one of many in recent weeks as the Texas-based company prepares to launch the Space Force’s mission known as Victus Nox ― Latin for “Conquer the Night” — to demonstrate the ability to build a satellite, integrate it onto a rocket and place it in orbit on rapid timelines.

Last September, the Space Force awarded Firefly a $17.6 million contract to provide launch services for the mission and entered a separate agreement with Millennium Space Systems, a Boeing subsidiary, to build a small satellite in just eight months that will fly on Firefly’s rocket. Millennium declined to provide the value of its contract.

Weber told C4ISRNET in an interview that the company will soon move out of the test phase and the alerts it receives from the service will no longer be practice runs.

“At some point, they’ll point at us and say, ‘You’ve got 24 hours — launch,’” he said April 17 at the Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colo. “And then we’ll be ready.”

Millennium will receive a similar notification, signaling that the company has just 60 hours to ship the spacecraft to Vandenberg Space Force Base in California and work with Firefly to integrate it with the company’s rocket.

The scant details about the timing of the launch order and the rapid delivery schedules are intentional, as the service wants the mission to closely resemble the operational conditions under which it would use the capability, dubbed Tactically Responsive Space, or TacRS.

Lt. Col. Mackenzie Birchenough, who leads the TacRs program, described the service as being in the “walk” phase of a “crawl, walk, run” trajectory. Victus Nox will be its second such mission — the first occurred in 2021 — and the Space Force is planning a third effort for next year.

“The ultimate goal for us is to get to an enduring TacRS capability by the 2025 or 2026 timeframe,” Birchenough said during an April 20 panel at the Space Symposium.

An “enduring” capability would be used for two primary purposes: to quickly launch satellites in response to threats in space — whether man-made or environmental — and to augment a system that was degraded or destroyed, she said. That could mean having a spare satellite on orbit that could be turned on or maneuvered into position as needed, working with commercial partners to buy data in a crisis or, as in the case of Victus Nox, have a satellite on the ground that’s ready to be launched on demand.

“I think we’re moving away from what the idea may have been in years past of you’re just going to buy a bunch of satellites and they’re going to sit in some actual barn somewhere . . . to the idea that we can pull something off that production line very quick and have it ready to go,” Birchenough said.

While a 24-hour turnaround time is the goal for Victus Nox, Birchenough said she expects the service will, one day, move even faster.

“If you ask folks out here today if they thought it was realistic that we’re going to hit 24 hours sometime in the next six months, I would probably get some varying responses,” she said. “I think being able to shorten those timelines is definitely possible. And from an operational standpoint, I think the need is going to be less than 24 hours in the future.”

Courtney Albon is C4ISRNET’s space and emerging technology reporter. She has covered the U.S. military since 2012, with a focus on the Air Force and Space Force. She has reported on some of the Defense Department’s most significant acquisition, budget and policy challenges.