Days after Iran’s unprecedented and largely unsuccessful bombarding of Israel, the U.S. and U.K. levied additional sanctions on the regime’s manufacturers and sources of materiel.

The joint move, made in direct response to the attack, targeted 16 people and two organizations supporting Tehran’s flowering arms industry, according to the Treasury Department. They include those who work on behalf of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and its unmanned aerial vehicle production arm.

The economic slap is meant to debase Tehran’s growing source of cash and cachet: weapons. Drones such as the Shahed and Mohajer, missiles, and their derivatives have been spotted or reported in the hands of Russian, Sudanese and Houthi forces, among others.

“We’re using Treasury’s economic tools to degrade and disrupt key aspects of Iran’s malign activity, including its UAV program and the revenue the regime generates to support its terrorism,” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in a statement April 18. More than 600 people and entities tied to Iran’s “terrorist activity, its human rights abuses and its financing of Hamas, the Houthis, Hezbollah and Iraqi militia groups” have been dinged in the last three years, she added.

RELATED

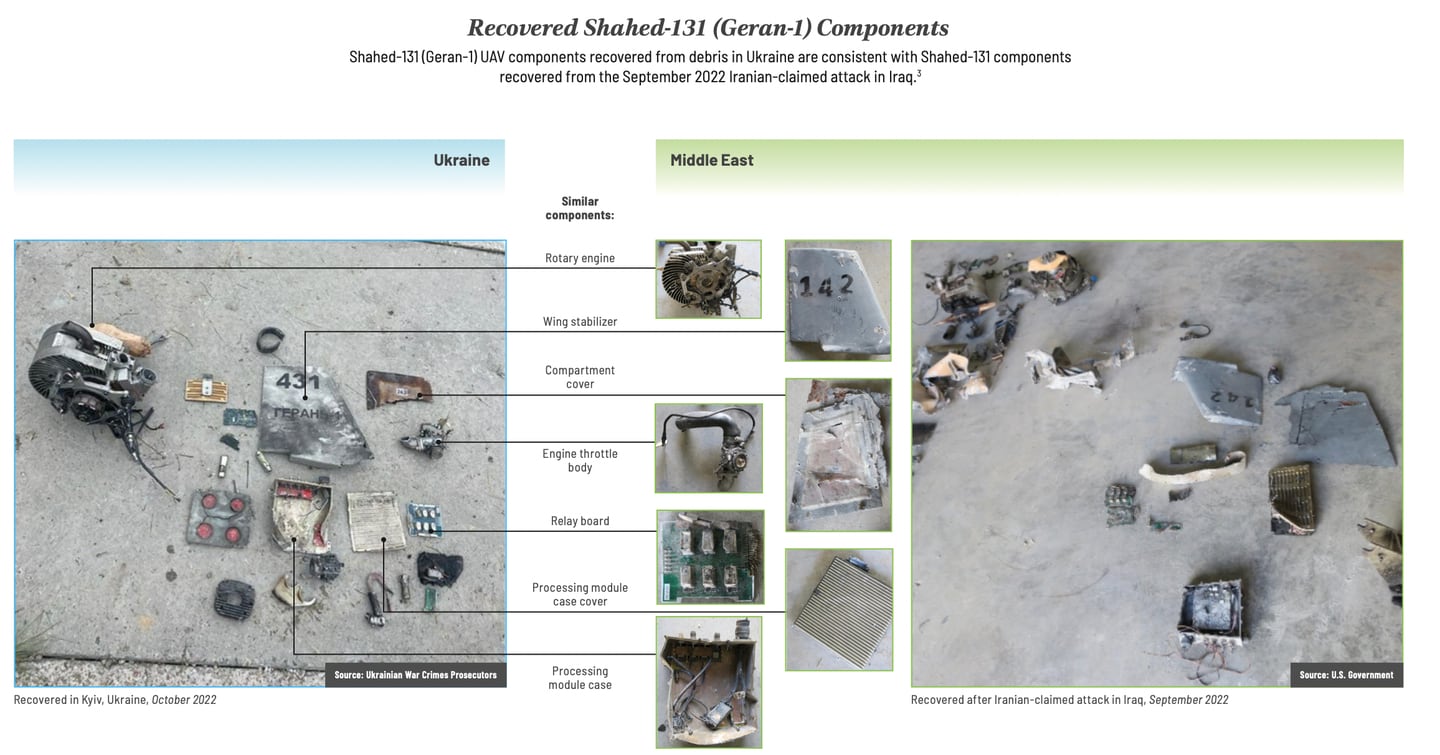

The international reach of Iranian technologies reflects its growing profile in the arms world and its goals of international influence, U.S. defense officials, outside analysts and defense industry executives told C4ISRNET. Parts of UAVs recovered in Ukraine and Iraq, analysis of military parades in Yemen, reports of transfers to the African continent, interdicted shipments in the Gulf of Oman and footage of production lines in Russia underline its ambition.

“Iran used to be a customer,” U.S. Navy Rear Adm. Mike Brookes told C4ISRNET during the Sea-Air-Space defense conference in Maryland. “Now, they are a producer and proliferator, and I think Russia is a great example.”

Four continents

Iran’s weekend barrage comprised roughly 170 drones, 120 ballistic missiles and 30 cruise missiles, according to Israel’s armed forces. Almost all the overhead threats were intercepted, with support from the U.S., U.K., France and others.

The Shahed appeared to be the salvo’s centerpiece. The one-way attack drones are assembled using simplistic parts — including from Western sources — and are capable of flying more than 1,000 miles with warheads weighing dozens of pounds. Their popularity is booming.

Iran has since 2022 supplied Russia with more than 1,000 Shahed and Mohajer UAVs, according to U.S. estimates. Footage of Russian production lines, buttressed by Tehran’s expertise, surfaced online earlier this year. On display were rows of black and grey Shahed clones known as Geran: airframes with triangular bodies, rounded spines, stubby nose cones and vertical stabilizers extending above and below the wings.

Shahed lookalikes known as Waid have also been adopted by Houthi rebels. The Defense Intelligence Agency documented the commonalities, and in a recent appraisal of worldwide threats warned Iran would lean on partisans to do its bidding. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps maintains a division dubbed Department 8,000, which develops UAVs and provides training to outside forces.

“Iran pursues interests, maintains depth and extends its reach through a network of militant proxies,” said Brookes, who serves as the commander of the Office of Naval Intelligence. The organization collects, analyzes and distributes information about foreign fighters.

“Iran currently proliferates weapons throughout the region and is becoming a burgeoning global proliferation risk,” he added. “Ten years ago, Iran was a local threat. Today, it is a regional menace with much broader malign-influence activities.”

Militaries and extremist groups are increasingly deploying drones and other unmanned systems to surveil and attack targets from greater and safer distances. Explosive drones can supplement missile stockpiles, as well, offering users a cheaper and less complex option.

Iranian contractors and government officials have picked up on the market demand, frequenting arms expos and other events in Russia, Iraq, Qatar, Serbia and Saudi Arabia, according to Behnam Ben Taleblu, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies think tank.

Iran showcased its Shahed-149 Gaza drone at the 2024 Doha International Maritime Defence Exhibition and Conference. It resembles the MQ-9 Reaper, made by U.S.-based General Atomics.

RELATED

“Iran is gearing up to go from arms proliferator to arms seller,” Taleblu told C4ISRNET in an interview. “With Iranian weapons like drones — be they unmanned combat aerial vehicles or one-way attack drones — spread across conflict zones in four continents, the regime is ready to share battle-proven but lesser-quality alternatives to current day military technology at half the price and with no regulatory hang-ups.”

In short, he added, Tehran is “quietly positioning itself as arms supplier to the third world.”

Here to stay

The ordnance flung at Israel is the latest evidence of the allure of drones and their ability to level the playing field. Taleblu has described them as the “poor man’s cruise missile,” exemplifying that quantity has a quality of its own.

A Shahed drone can cost tens of thousands of dollars. Sophisticated missiles or interceptors, like those relied upon by warships in the Red Sea, can cost many times more and are fewer and farther between. The U.S. Navy has expended close to $1 billion in munitions in the half-year its vessels have been patrolling the waters in the Greater Middle East.

“Israel, U.S. and its allies were fortunate enough to intercept 99% of Iran’s attack with limited damage and injury, but this is another sign that the use of UAVs on the battlefield are here to stay,” Andy Lowery, the chief executive at directed-energy company Epirus, told C4ISRNET. “And the tactics our adversaries employ when using UAVs will continue to get more sophisticated with the use of AI-enabled drone swarms.”

The danger drones and other unmanned technologies pose is factoring into U.S. military modernization. Counter-drone armaments including directed energy are in high demand.

The U.S. Army in 2022 inked a $66 million deal with Epirus to supply the Leonidas high-power microwave weapon in advancement of the service’s Indirect Fire Protection Capability venture. An initial prototype was delivered 2023. The company is also expected to test its products against boats and motors in an upcoming naval exercise, taking a cue from recent Houthi attacks involving explosives-strapped unmanned surface vessels.

“The munitions that were used to defend against the attack are not infinite. There will be supply chain, logistics, and budgetary constraints to resupply,” Lowery said of the Iranian onslaught. “From a strategic standpoint, this attack demonstrates the benefit of having a counter-electronics solution with an unlimited magazine as part of a layered defense approach.”

The Pentagon is spending an average $1 billion a year developing directed-energy weapons, according to the Government Accountability Office, a federal watchdog. At least than 31 directed-energy projects were underway across the military as of this year.

Army Gen. Michael Kurilla, the leader of U.S. Central Command, has said he would welcome additional directed-energy weaponry to address overhead threats: rockets, artillery, mortars. He’s also said attack drones are at the heart of a “nascent military partnership” between Iran and Russia.

The U.S. Army this year dispatched three Stryker-mounted lasers to Iraq for evaluation. A fourth will soon follow.

“Because the evolution of counter-UAS is extremely fast and the threat is real, as seen in Iraq and Syria up until February,” a defense official told C4ISRNET last month, “deployed units can use this environment to operate, test and further develop these new capabilities in real-world conditions while identifying crucial lessons on the impact of operational surroundings.”

Colin Demarest was a reporter at C4ISRNET, where he covered military networks, cyber and IT. Colin had previously covered the Department of Energy and its National Nuclear Security Administration — namely Cold War cleanup and nuclear weapons development — for a daily newspaper in South Carolina. Colin is also an award-winning photographer.