WASHINGTON — U.S. Army Spc. Jeremy Boyle started creating software when he was 10 years old. Curious how websites were made, Boyle taught himself how to code using online video how-tos.

“I was just always that person that would be looking at tutorials online, trying to figure out how to do it,” Boyle told C4ISRNET. “It just helped me build my way. That went from websites to creating mobile applications to creating Android software — a whole range of variety of things before I went into the Army.”

The medic is learning platform engineering skills as one of the inaugural cohort of about 25 soldiers at the Army Software Factory in downtown Austin, Texas. Boyle is one of many soldiers with software development skills the service theorizes it has within its ranks who could help with its software coding talent shortage.

The Army — and the U.S. military at large — have a ripe need to train software creators to use the DevSecOps development process to roll out digital tools more quickly, improve them and build on them after an initial release. The Army factory, funded through a portion of $26 million allotted for cloud modernization in fiscal 2021, joins similar efforts by the Air Force, which has established more than 10 software factories across the country to prepare for the digital age.

The Defense Department pays billions for software, estimating it will spend $15 billion over five years ending in 2023 just to maintain the software it already has.

As warfare becomes more electronic, weapon systems will become more software dependent, and the military needs people to code applications faster to meet commanders’ needs.

After their training, the software developers with the Army will be able to help create applications for logistics, mission command, soldier quality-of-life and tactical mission scenarios.

By making use of talent already in the ranks, Army leaders believe a “for soldiers, by soldiers” approach will help the developers eventually deliver more useful software to users, while saving money on high-priced contractors.

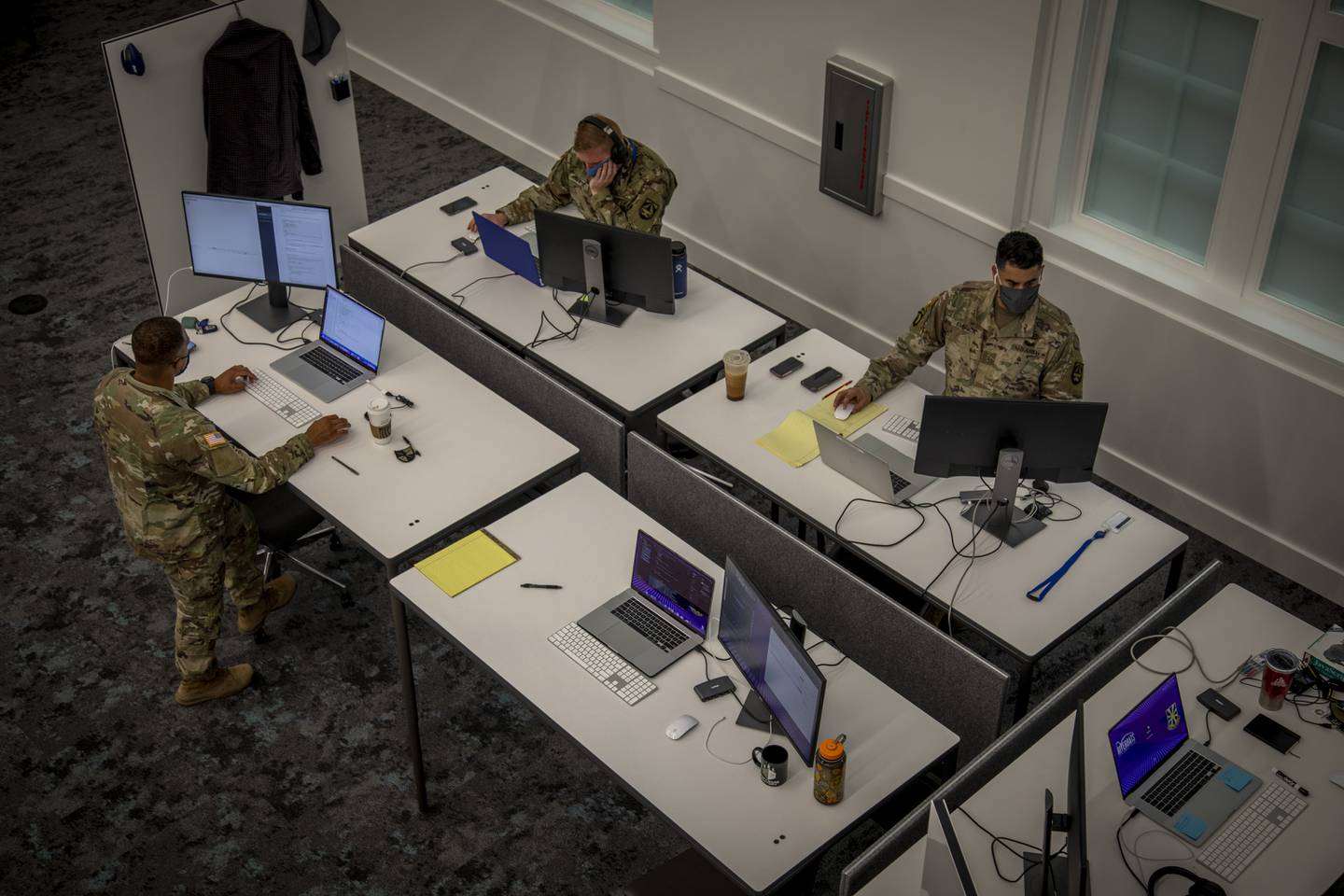

The software factory, hosted by Army Futures Command, ditched the service’s hierarchical conventions to create a startup-esque culture in which ranks are largely insignificant and soldiers call their superiors by their first names.

“Jeremy comes from ... one of the lowest ranks in the Army as an enlisted man, and yet he, by all accounts, could be the teacher of the platform engineering track,” said Maj. Vito Errico, the factory’s co-director.

“It goes back to that original assumption that the talent is here in the Army, and do we really care about the ranks or do we care about retaining and building the skill set?”

Prototyping a new culture

The facility in the shadows of Austin’s skyscrapers provides a contrast to spartan military bases with rigid formality standards — often located in less populated areas.

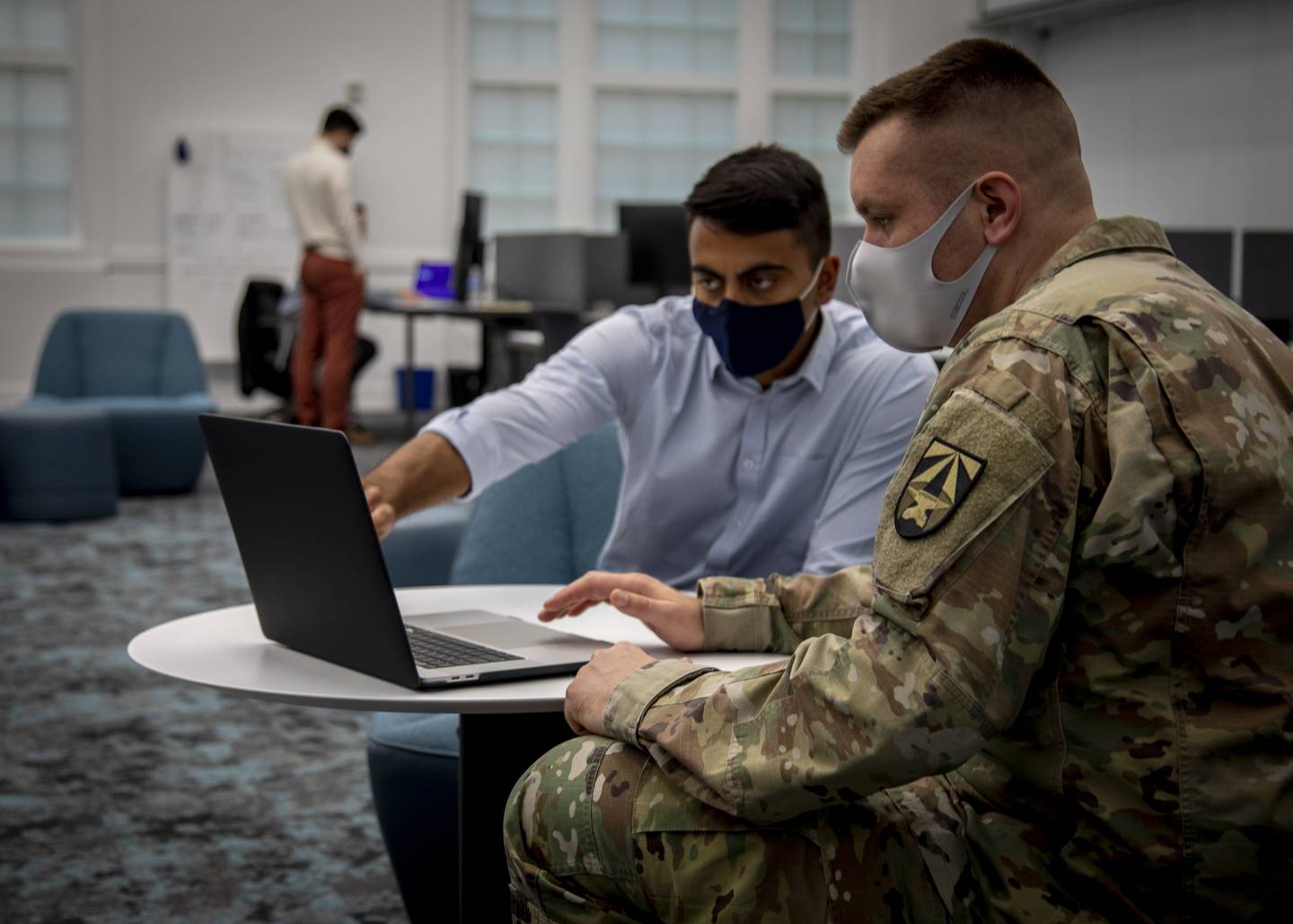

Beyond the first-name custom, the informal culture is evidenced by standing desks, open-concept workstations and meetings in cushioned chairs that look more college library than military base.

Civilian clothes are acceptable at the factory, situated next to the Texas Capitol and walking distance from the University of Texas. Officers don’t have the final say. The whole point is that the Army needs the software skills; it doesn’t matter what rank they come from.

Soldiers in the first cohort arrived in Austin in December. The service plans to keep soldiers at the facility for a three-year rotation, and they will take software development courses to learn the tradecraft and sharpen skills. After the rotation, the goal is for the soldiers to join a command and develop software solutions for that organization’s problems.

The software factory, hosted by Austin Community College, has tracks the soldiers follow: product manager, user experience and user interface designer, software engineer, and platform engineer.

They hone their practical skills with hands-on prototypes. After finishing about four months of coursework, the soldiers remain in Austin for the rest of their rotation, working one-on-one with a subject matter expert and on product development teams tasked with solving Army software challenges.

“The idea behind moving them here and putting them in one spot for three years is so that we can guarantee that we immediately utilize the skill sets that we just taught them,” Errico said. “And that’s a pretty big point to make sure that those skills don’t atrophy right away.”

1st Lt. Haley Steele, who is on the product manager track, came to Austin from Joint Base Lewis-McChord, where she was a platoon leader in a signal company. Steele, like Boyle, is an example of a soldier who had learned basic software skills. A computer science major at West Point, she helped develop an iPhone augmented reality application that taught users about the institution’s history.

Errico said he’s looking for people who “have emotional intelligence and empathy — critical skills to operate differently than everybody else, to operate in a rank-agnostic environment — and can thrive in a team.”

The work is different than any Boyle has experienced since he joined the service. In the new culture, leaders higher in the chain of command don’t view the soldiers as low-ranked grunts, but as collaborators with valued ideas.

“They sit down [and] listen to what I have to say, and they value what I have to say,” Boyle said. “It was a little bit of a culture shock and a little bit of a change, but I think it is something for us to be agile and do everything that we need successfully.”

Steele, as an officer, had a similar experience and says the culture has created an organization that is more open to innovative ideas.

“It was interesting at first, especially when you’re calling majors by their first names — that was definitely a little bit weird,” Steele said.

“But I think it’s been really great for the organization as a whole because it really puts everyone on a level playing field, where anyone’s idea can be the best idea, and then you can take that and you can run with it and come up with a solution that you wouldn’t have come up with normally, just because they’re a junior enlisted.”

The second cohort of soldiers is expected to move to the factory in July. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, 60 percent of instruction has been virtual. First cohort soldiers would like more in-person instruction, as soon as that’s possible, Errico said.

For now, the software factory is focused on proving that its hypothesis is true: that the Army can upskill recreational software developers in its ranks. The organization wants to show that soldiers can work for commanders in product teams outside the factory, while seeking a dedicated program line in the fiscal 2023 budget.

“As we prove it to be successful that soldiers can operate independently as product teams, with the right tools and skill sets, you’ll see us begin to partner with larger commands in the field and grow their own organic capabilities, with the right commanders at the right bases under the right conditions methodically,” Errico said. “I think one of the biggest sins we can commit is trying to grow too fast.”

Andrew Eversden covers all things defense technology for C4ISRNET. He previously reported on federal IT and cybersecurity for Federal Times and Fifth Domain, and worked as a congressional reporting fellow for the Texas Tribune. He was also a Washington intern for the Durango Herald. Andrew is a graduate of American University.