Later this year, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency is expected to launch a series of risk reduction payloads into orbit to help pave the way for an experimental program known as Project Blackjack.

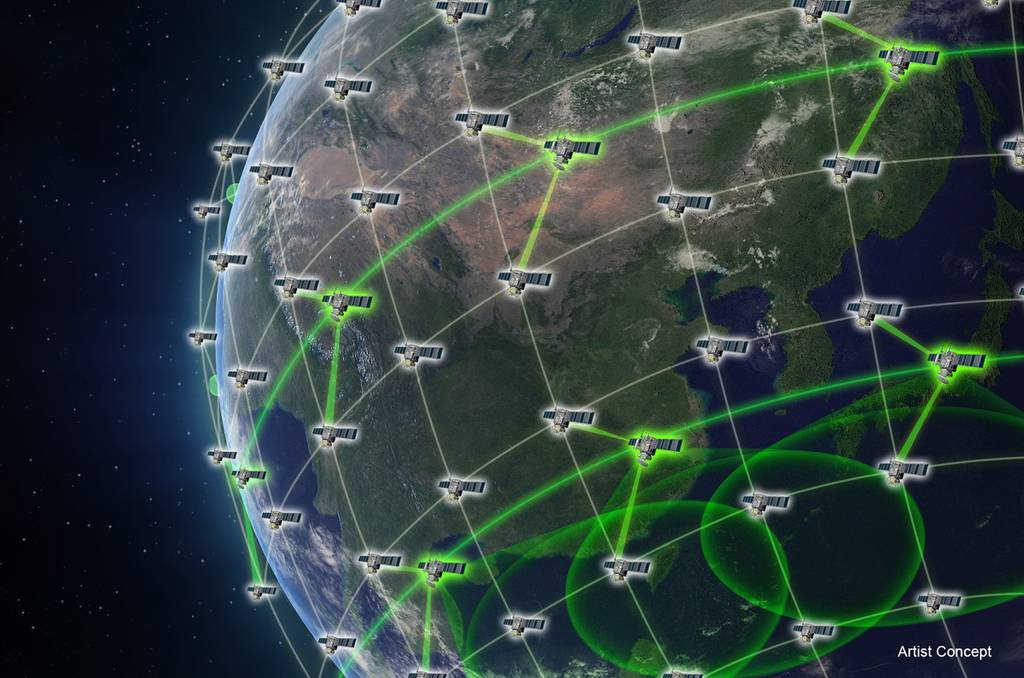

With Blackjack, DARPA wants to demonstrate the military utility of a large constellation of small satellites operating in low earth orbit. These satellites will connect with each other on orbit over optical intersatellite links, forming a mesh network in space. That network will be able to deliver sensor data collected on orbit to terrestrial war fighters in near-real time.

And while Blackjack won’t transition to a program of record, Defense officials have made it clear that the technologies it will demonstrate will pave the way for a DoD-specific mesh network on orbit being built by the Space Development Agency.

RELATED

DARPA has issued a flurry of contracts in recent weeks as the agency prepares to launch risk reduction satellites later this year and then it’s first Blackjack payloads in 2021. In May, Blackjack Project Manager Paul “Rusty” Thomas spoke to C4ISRNET about the current state of the project, who the agency is partnering with for payloads, and how it feels to see this mesh network concept become a reality.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

C4ISRNET: First, can you provide an update on where Project Blackjack is right now?

THOMAS: Blackjack, in summary, is turning the corner from our phase one exploration of what type of commercial technology we can use to leverage the entire military utility of P-LEO, hopefully disruptive approaches to constellations and network architectures, [and] space mesh networks of the future. And we’ve recognized where some of the key risks are. We’ve also recognized that we’ve got a great opportunity to demonstrate proliferated LEO with a sub constellation in the 2021-2022 time frame. So the current position of Blackjack is tying up all the loose ends at the end of our phase one contract, lots of buses, lots of payloads, the vast majority [of which] did a great job for us and got a lot of great offers—more options than I think will ever get funding or even time to chase. We’re looking great.

Now the tough job is: okay, how do we give the best and most comprehensive demo that really nails down some of the risks that P-LEO has, which is substantial. We’re going to have a high level of autonomy, but we don’t have a huge amount of manpower on the ground. How do we get the space mesh network to work where we move broadband data with low latency globally [while] minimizing ground links? How do we actually put a lot of our [processing on orbit], and have the space sensing and the processing of that data all up in space?

So we’ve identified technology problems areas and now phase two is starting to ramp. I think we’ll be able to make some announcements later this year about what we’re actually going to fly in ’21 for key demonstrations with that sub constellation of 10 to 20 satellites. And that’s all looking very, very positive in my mind. Along the way, we’ve learned, ‘Hey, these might be key risks,’ and we’ve established a set of risk reduction, smaller missions, smaller satellites — we’ve got cubesats all the way up to 100-150 kilogram spacecraft that can demonstrate some of the key pieces, whether it’s the very powerful processor supercomputers in space, in orbit, that we want to put up to provide that type of processing capability, or whether it’s the optical intersatellite links that will provide a space mesh network that will provide gigabits of connectivity between satellites. As we identify those, we’ve actually been able to put together using commercial approaches the ability to bring new technology and get it integrated and into space in months or a year’s time instead of years.

That’s why you saw that press release, where we talked about the Mandrake 1, the Mandrake 2, [...] the Sagittarius-A* and the Wildcard. Those four programs are going to put at least about five satellites up and we’re going to demonstrate starting in August with Mandrake 1 later this fall.

Later this year, we’ll have the first one, the Mandrake 1 launch, and then Mandrake 2—working that one with SDA. Very, very awesome partner working with us to get those intersatellite links and the optical pieces’ risk pounded down, and then move into the Wildcard and Sagittarius-A* missions early next year. And if those all go well, we’re looking like we’ll send our first two full blown spacecraft up in the fall of ’21 and be able to put a subconstellation up in ’22. We’ll do some pretty amazing things with that demonstration.

C4ISRNET: Earlier you said Project Blackjack is really turning a corner right now. For us, it seems like it’s ramped up very quickly over the last month or so.

THOMAS: It definitely has. I drive a Tesla to work and I always say it’s like driving a rocket to your job. And that’s what it’s like, putting the pedal down on the Tesla where that infinite amount of torque of your electric motor starts to really accelerate you. That’s exactly what it feels like to be at Blackjack.

C4ISRNET: My understanding was that the first flights were supposed to be in ’21, or at least that was the earlier plan. What allowed you to push up the first launches to August/September?

THOMAS: The risk reductions don’t have all the capability that the Blackjack node is going to have. The Blackjack node is going to show how we can use these commoditized commercial approach buses to work for a wide variety of payloads. It’s going to have optical intersatellite links, a very powerful processor, an AI-enabled capable supercomputer, and it’s going to have a sensor that has high military utility. All those features have to be on before an actual Blackjack node can turn on, interface, connect to its next door neighbors, and start doing a mission with a constellation autonomy turned on, with all the reliability and availability. All the utilities are at the constellation level. An individual node is just one more piece that can come and go whether you have a liability issue or some problem, your resilience is at the fact that you have a large mesh network, kind of like we have internet on the ground—we can lose individual nodes and it doesn’t do anything.

So Blackjack nodes that we talked about for late ’21 have to have all those key elements on board. The reason we have these early launches is because we have all these key technologies and DARPA hard pieces that are coming together, we really want to show that we can demonstrate those elements in space earlier.

The Mandrake 1 doesn’t do all of those elements. It just looks at the supercomputer in space and chips we want to fly and show that they can operate in the environment of low Earth orbit. If that works then that means the computers we’ll launch in fall of ’21 have a very high probability of success, or a higher probability of success.

And then same thing with the Mandrake 2. That’s the one with SDA where we’re showing the optical intersatellite links. There are plenty of wonderful optical intersatellite links technology-wise that are fairly large apertures and, you know, [cost millions of dollars]. For a proliferated low Earth orbit architecture you need to get that down by an order of magnitude. Size, weight, power and cost all need to get in a better box than what they are, and that’s what DARPA is doing in advancing the technology, showing that we can fly these systems that will work in a P-LEO architecture. Mandrake 2 is focused just on that — the optical intersatellite links versus the software defined radio for Wildcard and then the data fusion, kind of big brain in space, that we’re doing to Sagittarius-A*. So those almost look at individual pieces of the puzzle that add up to a Blackjack node. Sum them up and now they all work great and we have a great mission next year. If we have issues with any one of these, we can turn the dial, adjust our architecture and our hardware on the ground before we launch the first two and actually go up with a higher chance of mission success on these first two satellites because of all the individual risk reduction missions we’re doing this year.

C4ISRNET: We heard recently that Special Operations Forces Command (SOCOM) has been partnering with you on aspects of Blackjack. Who are some of the other DoD partners you’re working with on Blackjack?

THOMAS: As an active Navy Reserve intelligence officer, I deployed with Naval Special Warfare to the CENTCOM area, to Iraq in 2008. I’m very familiar with the SOCOM mission set, very much interested in helping them get their job done in a tactically relevant way. Blackjack by definition, [takes] tactically relevant information and delivers [it] to tactical warfighters in seconds or minutes from when it hits the sensor, and SOCOM’s mission is all about doing those type of tip of the spear missions where you can really help with the cost of the system overhead, whether it’s comms or sensors. The wonderful set of potential approaches with SOCOM — I don’t want to talk about anything specific there just because I do recognize that it’s key to what’s going on.

The main thread is we started with a wonderful partnership with [the Air Force Research Laboratory] out in Albuquerque — and they basically got us off the ground with their deputy program manager that’s on site currently with me here in DARPA HQ in Arlington. They’ve been providing early support in multiple ways to get the program off the ground quickly.

[U.S. Space Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center] in LA stood up a CASINO program office that could actually stand as a transition path, and they’ve been spectacularly supporting Blackjack, standing with me every day. I have a telecon with them to their senior folks once a month. I talk to their program manager multiple times per week. So we are in sync with how I am working development of P-LEO technologies and risks and what I’m doing to be able to develop and what I will be able to transition into the CASINO path that SMC is managing. So that’s that’s my second big one.

Third, SDA was of course stood up on using P-LEO and a lot of the architectural elements I’m doing, you know? There’s never talk about a straight transition path—Blackjack can go many directions—but I certainly am working with SDA on a regular basis to develop all the key technologies, include that Mandrake 2 which is a strong partnership with SDA specifically because they also recognize how important the optical intersatellite links and the broadband low latency, no RF spectrum issues type of communication satellites of the future for P-LEO is.

I also am working with the Army. The two payloads that they’re actually working on [will specifically] deliver tactical war fighter information — ISR data — directly to the war fighter. And I’m briefing them on a regular basis.

I also talk to MDA on a regular basis as we go back and forth on the various Missile Defense Agency mission sets and areas I could help reduce risk with. So all of those folks are in regular contact with me, I'll say almost daily, as we work through how Blackjack can help define a new architecture, be disruptive and show how we can augment systems that are out there, maybe do things differently with a little extra resilience, or significantly more resilience and then also work toward what would be a good demo for the various services and agencies.

C4ISRNET: Last year we saw the SDA stood up, more and more verbal buy-in to P-LEO for various missions, and the declaration that an on orbit mesh network will play a key role in Joint All-Domain Command and Control. Are you surprised at how quickly DoD has embraced this P-LEO model before you even have had to completely demonstrate it?

THOMAS: It’s always surprising when things move faster than you expect of course, but that’s a good thing. That’s what we’re trying to do here. DARPA’s job is of course not to build an operational system. Our job is demonstrate key risks and pound that out like I said earlier, so that operational folks can have some confidence and proof of existence that these things are going to work. And so I am very encouraged by this.

I wouldn’t say I’m very surprised. I have been a believer in proliferated LEO since I started at Motorola in ’93 on Project Iridium, the Iridium Mark I. And I saw what that could do technologically. And you know, Motorola had to go through bankruptcy and had some problems with Iridium at first, but it was a technological achievement that really changed my thinking in a big way. We saw how we could build a standard satellite and mount it without any changes to a Delta II, a Proton Russian rocket — back then we could even launch on Chinese rockets, and we did. All the standard satellites could go on any one of those folks. Production line approaches — there was all these things you could use when you go to a smaller satellite than what we do with these big, large, exquisite satellites and put them on a production line approach. And so I’ve been a believer in that since the early 90s. I’ve cut my teeth as a Motorola engineer, both when I was working with with the Sunnyvale folks to build the bus — Lockheed built the bus for Iridium — and then I worked on the launch team to get that launch cadence up to put up 80 plus satellites in one year from three different continents. And it all worked. So I saw that happen. I also saw the failures that happened with the financial piece. But they came through that and they’ve been in service ever since it got there.

I was at Teledesic in the early 00s, and that’s where Bill Gates, Craig McCaw we’re very interested in trying to build this internet of sky approach, and a few technical issues and the Dot-com crash stopped that, but still, the power of it was absolutely there. Anybody who worked there knew that this was an architecture that had a lot of power. So I think what’s happened the last few years [is], we’ve continued to miniaturize, we’ve continued to find ways to bring commercial approaches and go fast approaches to the space domain, and now DoD is taking a lot of that up. I think you’ve got to give some credit to SpaceX, who has shown how you can do different approaches using commercial approaches in the launch area now with the success of getting the Starlink satellites up. Those are all coming to fruition now. I think the architecture has shown its promise for many years and the technology is getting to the point we can really leverage it. So I think it’s all those years of meshing, and you’re starting to see now DoD is engaging on that front also and taking advantage of all that’s come before.

So I guess I’m not surprised. I’m also surprised it didn’t happen five years ago.

Nathan Strout covers space, unmanned and intelligence systems for C4ISRNET.