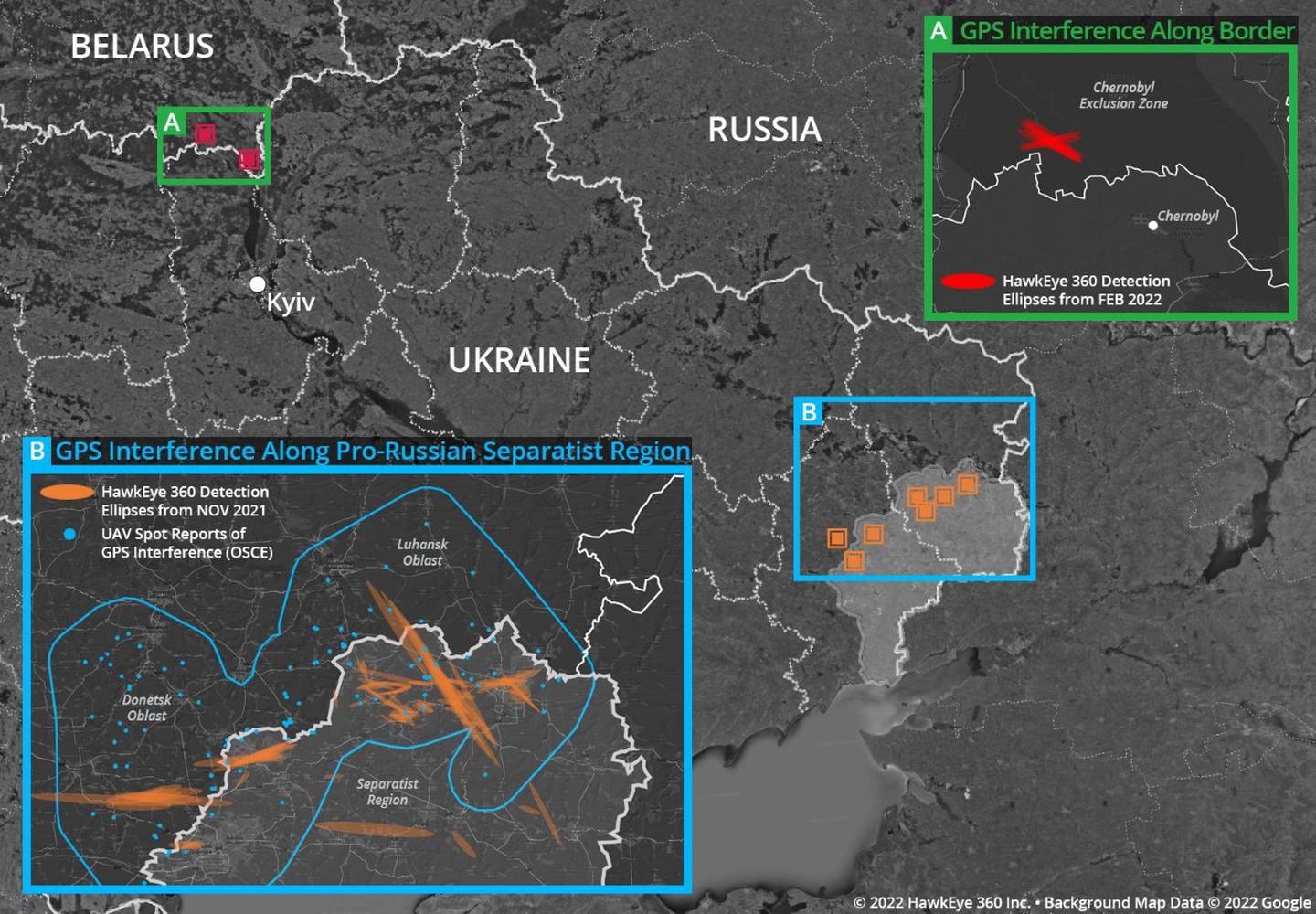

In the months leading up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, radio frequency detection and analytics company Hawkeye 360 began picking up GPS interference signals across Eastern Europe with commercial satellites.

As analysts reviewed the data, they discovered that significant GPS jamming near Luhansk and Donetsk in Ukraine was disrupting unmanned aerial vehicles operating in the region. Then in late February, just before Russia invaded the country, analysts detected interference near Ukraine’s border with Belarus, north of Chernobyl.

From Hawkeye’s detection of GPS interference over Ukraine to satellite images showing a 40-mile-long Russian military convoy headed into the country, commercial space capabilities are providing real-time insight into Russian military activities and providing support to Ukrainian forces, humanitarian organizations and journalists covering the invasion. They’re also providing a present-day case study for ongoing policy discussions about how much of this intelligence should be shared in open-source environments and how the U.S. should respond if commercial assets are targeted by an adversary.

COMMERCIAL SPACE IN UKRAINE

The impact of commercial space services on the conflict in Ukraine was immediate.

Within days of Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion – and following a request for satellite internet support via Twitter from Ukraine’s digital minister Mykhailo Federov – SpaceX began sending Starlink terminal kits to Ukraine and has since sent thousands, according to a report from CNBC.

In another high-profile example – which also transpired, at least in part, over Twitter – Federov called on commercial satellite companies to share imagery and data directly with Ukraine and, according to the Washington Post, at least five providers have agreed to cooperate.

BlackSky, a geospatial intelligence company that offers high-revisit imaging from space, is currently “supporting a number of organizations around this particular event,” CEO Brian O’Toole told C4ISRNET. While he wouldn’t name those organizations, they include government customers and humanitarian organizations that are looking to deploy resources in the region, as well as media covering the crisis and commercial customers concerned about economic and supply chain impacts.

The war in Ukraine is certainly not the first major conflict where commercial space capabilities have been a feature, but experts say advances in technology have enabled these systems to play a much larger role than in the past. A February report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies highlights this development, noting that the last 10 years have seen significant advances in microelectronics, small satellite technology and reduced launch costs converge with improvements in key capabilities like synthetic aperture radar, radio frequency mapping and data storage and analytics.

These technology advances have “the potential to shatter paradigms” of how the military thinks about collecting data on an adversary’s movements, the report said.

“Rather than relying exclusively on high-demand, low-density government-owned national assets, commercial sensing offers orders of magnitude more coverage and revisit rates that can augment and queue the sensing capabilities provided by more exquisite government-owned and government-operated systems,” the report states.

Todd Harrison, director of the Aerospace Security Project at CSIS and one of the report’s authors said this “revolution” is part of what has made open-source information sharing such a prominent feature of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“That is what has really caused this revolution in commercial space remote sensing capabilities and brought us to the point where we are today,” Harrison said. “And there are a lot of policy implications that go with that that we have not necessarily thought through and prepared for up until this point.”

INTELLIGENCE SHARING

One of the more prominent policy questions raised by the ongoing conflict involves the sharing of intelligence that has traditionally been classified or controlled by government agencies.

Kari Bingen, Hawkeye 360′s chief strategy officer and the former principal deputy under secretary of defense for intelligence, said during a recent event at the International Institute for Strategic Studies the U.S. government should take advantage of the burgeoning commercial market and build policies that normalize greater sharing of information.

“From a space and intelligence perspective, it’s phenomenal to see the unprecedented sharing of intelligence right now,” Bingen said. “Clearly, there’s an urgency of the moment right now. I think the question going forward will be, will we sustain some of this going forward in our policies and institutionalize this kind of sharing?”

The U.S. has put constraints on companies that prevent them from sharing imagery over certain regions or of a certain level of quality, said Brian Weeden, director of program planning at Secure World Foundation. Many of those restrictions have been lifted in recent years through measures like the Trump Administration’s Space Policy Directive-2, but some still exist, Weeden noted, pointing to recent reporting from Breaking Defense about the government using contractual language to enforce licensing controls.

Some of the government’s concerns about open-source intelligence revolve around controlling the narrative of a conflict, Harrison said. While the public release of imagery and other information has worked in the U.S. government’s favor in this particular conflict, that may not be the case in future scenarios.

“I think that in the aftermath of this, we’re going to have to take into account in our national security strategy that the world has become more transparent and we cannot necessarily control the narrative, nor can our adversaries,” he said.

There are also fears that sharing too much information could interfere with military strategy or operational security in certain scenarios.

Col. Ben Ogden, a space operations officer at the U.S. Army War College, said the uncontrolled release of high-quality satellite imagery could take away the element of surprise in a future military operation.

“When you talk about operational security, there are going to be so many satellite imagery possibilities from commercial companies that national security efforts – whether it’s troop movements that we would like to do in support of our interests – will not go under the shade of night or there will not be much of an operational surprise anymore,” Ogden said during an event in early March.

Commercial space capabilities reportedly played a role in the Iranian military’s January 2020 attack on Ain al-Asad Air Base in Iraq. More than a year after the attack, which damaged equipment and injured more than 100 people, 60 Minutes reported that Iran had used commercial satellite images to monitor the installation.

Even with these concerns, Bingen noted there is clearly a demand, even within the military, for more releasable intelligence. And Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is putting that demand signal on display and providing a use case for the role commercial space capabilities could play in the larger intelligence picture.

“The demand signal’s there,” she said. “We just now need the institution to respond with the disclosure policies, the processes.”

RESPONDING TO AN ATTACK

Another policy issue elevated by Russia’s war on Ukraine is how the U.S. would respond if Russia attacked a commercial space system providing intelligence in support of Ukrainian operations. Weeden said the question carries a particular weight given Russia’s possession and past demonstration of both destructive and non-destructive counterspace weapons.

“This is the first sort of modern conventional armed conflict between two opponents with pretty significant capabilities and at least one of them, on the Russian side, has a bunch of counterspace capabilities, so they can react to the use of space by the other side,” Weeden said.

Remote sensing companies have in recent weeks raised concerns that there isn’t a clear process for reporting an attack or collaborating on a potential response. J.R. Riordan, chief revenue officer at BlackSky, said the company spends “quite a bit of capital” on protecting its systems, noting that “there is no 9-1-1 phone call for us to say, ‘Help.’”

“We’re trying to make stronger doors, better locks and better protection, so that we can do that for our customers as well as protect our assets,” he said during the Satellite 2022 Conference in March.

While there are precedents and international laws around targeting civilians and third parties in an armed conflict, the lines are blurrier when it comes to space. John Hill, acting assistant secretary of defense for space policy, said international law doesn’t provide clear guidance on “what is permissible” in space.

“There is so much about what is responsible behavior in space that we’re figuring out as we go,” Hill said during the same conference.

He advocated for more deliberate engagement with operators across the space enterprise as a way to “create the content” and best practices around safe and responsible conduct in space, saying that work could eventually lead to international agreement.

Weeden said there has been some momentum in recent years to develop norms around responsible behavior in space, highlighting an upcoming United Nations “open-ended working group” meeting focused on space threats.

The first session is slated for early May and Russia had been expected to be at the table, but a Department of State official confirmed during a National Security Space Association event in March that Russia will not participate. Weeden said he expects the current conflict to feature heavily at the meeting, especially given Russia’s November anti-satellite test.

Courtney Albon is C4ISRNET’s space and emerging technology reporter. She has covered the U.S. military since 2012, with a focus on the Air Force and Space Force. She has reported on some of the Defense Department’s most significant acquisition, budget and policy challenges.